On Sunday, August 25th, 1918, the troops of the American North Russian Expeditionary Forces entrained at Brookwood, Surrey, in the south of England for Newcastle-on-Tyne to embark on ships headed for Russia. Brookwood is approximately six miles northeast, as the crow flies, of Camp Aldershot, Hampshire, and is the home of a major railway station in that area. The men probably arrived there via a train taken from the North Camp railway station.

In the three weeks that the 339th Infantry had been in England, they had had every military item in their possession replaced and anglicized by the British Expeditionary Command. Everything the American soldiers were issued, whether it was food, uniforms, weapons, or medical supplies, was inferior, inadequate, and of the lowest possible quality. Imagine if your life depended on a rifle that had inaccurate aim, jammed or broke frequently, and had to have a bayonet carried on it at all times, since it was manufactured without a scabbard...especially if your military training had been completed with a different, superior weapon. Imagine eating rations consisting of canned foreign corned beef, seven-year-old frozen Australian rabbit, "M & V" ("meat"--a glob of fat--and vegetables), powdered peas that needed two or three days of soaking in warm water, hard tack (which you couldn't break it with your fist), tea, jam (a concoction of ginger and rhubarb), and unsweetened lime juice. Suppose your medical supplies consisted of iodine, quinine, and laxatives, and your medical corpsmen had been trained mainly in rolling bandages and condoms. Suppose your clothing, while keeping out the cold, having been designed by arctic explorer Ernest Shakleton, was bulky, uncomfortable, and allowed for as much freedom of movement (while under fire) as the Michelin man's outfit. Imagine running on snow and ice in ill-fitting boots with slick soles and heels.

Most of these problems were yet to be discovered by the Americans until after they arrived in Russia. Meanwhile, the troops took the 270-mile train ride north to Newcastle-upon-Tyne in the northeast corner of England, south of the Scottish border, arriving in the late afternoon of the 26th. Here they embarked on three transport ships, the Tydeus, Nagoya, and Somoli, and were accompanied by the Czar carrying Italian and French troops headed for Murmansk. Sometime after midnight on Tuesday the 27th the ships slipped down the Tyne towards the North Sea, nine miles away. Besides the 339th Infantry, the convoy contained the 310th Engineer Regiment (the 1st Battalion), the 337th Ambulance Company, and the 337th Field Hospital. Bryan was aboard the Somali, an illustration of which appears here. At least one of the ships, the Nagoya, had just returned from a trip to India during which an outbreak of the Spanish Influenza occurred. The Nagoya was never quarantined or fumigated before taking on the Americans, and almost immediately the troops on all the ships became ill, Bryan included.

In a statement he wrote in order to obtain a disability pension from the military after the war, Bryan writes:

I had the influenza on the ship Solomimy sailing from New Castle, England to Archangle Russia Which left me in a weakoned condition,There were precious few medical supplies on board. Those that had been intended to be brought had been purposely discarded on the docks of Newcastle in order to make room for the cases upon cases of whiskey demanded by the British officers.

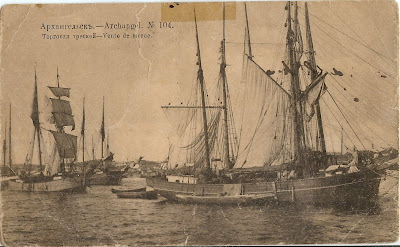

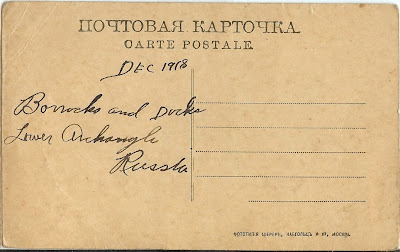

The convoy had meantime passed between the Shetland Islands and the bulge of Norway, through the Norwegian Sea, rounding the North Cape, and into the Barents Sea. By now, they had entered the White Sea, and it was here that the first death from influenza occurred. Soon those soldiers not too ill to come on deck could see "vestiges of islands of land," part of a 24-by-20-mile delta of the Northern Dvina River which flowed north to deposit its soil in the White Sea. At the entrance of the main channel, the convoy waited for a tug to guide them through the labyrinthine canals. Under the heavily overcast sky, there was nothing to see but miles upon miles of swampland, occasionally broken by stunted pine trees. Passing small hamlets and a small lumbering village, they finally arrived around noon on August 6th at the Port of Archangel (Arkhangelsk), a community of 40,000 strong.

At the docks of nearby Bakaritza, the ships began to unload their cargo, and the sick were moved to a primitive Russian hospital nearby, which filled quickly. Several days later, the Red Cross opened a hospital in Archangel and was also immediately filled. Some of the barracks had to take the overflow. In the month of September alone, 75 men died of influenza. By October, a convalescent hospital was opened in an old Russian sailor's home in Archangel, near the American headquarters.

Members of the 337th Field Hospital had practically no medical training. The conditions were primitive, to say the least. The sick lay dying on stretchers on the floors. The medical corpsmen took turns in shifts, one man watching in case of emergency, the other sleeping on the floor behind a stove. Whenever a patient died, the one would wake the other, and the two men would carry the corpse out to the hallway, to be picked up in the morning by a detail, which would transfer them across the bay to a new American cemetery in Archangel. One can see why Bryan refused to go to the hospital, and conditions there were likely more contagious than elsewhere. After three or four weeks, the epidemic ran its course; nearly 100 young Americans had died, most buried in Archangel, a few at sea on the trip over. Amazingly enough, none of the 337th unit died, although some had been very ill and were a long time convalescing.

Bryan revived soon enough and was immediately sent to the railroad front at Obozerskaya, although it was probably too soon for him to have fully recovered from his illness. We'll pick up with Bryan's adventures there after we hear next from his mother at home.

Other posts in this series:

1. A Polar Bear in North Russia

2. The Family of Angelo and Lula Robbins

3. Bryan and Marie - A WWI Romance

4. Bryan Gets Drafted

5. Basic Training at Camp Custer

6. Getting "Over There"

7. Bryan and King George V

9. A Letter from Mother - 25 Sep 1918

10. A Letter from Father - 7 Oct 1918

2 comments:

Miriam,

That is quite a story you tell! The Spanish Flu killed more people than those who died from other causes in the war, and actually killed more people than the dreaded bubonic plague had.

Janice

Janice, you're right there. What was so bizarre about the Flu was that the strong, and healthy were its main victims, rather than the old and weak, or the very young (although many of these died as well). If you read my post on my grandaunt Barbara Valk, there is some information about what scientists theorize was the cause behind that anomaly.

Post a Comment