Today I received a surprise in the mail: three CDs' worth of scanned pages and photographs from the scrapbooks of my paternal grandfather's sister. It is a treasure trove, and I am absolutely giddy over it! There is a large collection of letters, documents and photos from my Great-grandfather Robbins' service in the American North Russian Expeditionary Force during and shortly after World War I. I will be sharing these treasures with my readers in the near future, and to give you background, I encourage you to read his AnceStory (biography)

here.

I am also posting an article below which I submitted to the

Eastern Washington Genealogical Society's 2005 literary contest "My Favorite Military Ancestor," for which I won a second-place prize of $50 towards purchases at my favorite genealogical publishing company. This should give you a better idea of why American forces were in North Russia (and Siberia)...a fact that the U.S.S.R. used against us in their history books during the Cold War. After all, we had invaded them once; why wouldn't we do it again?

----------------------------------------------

William Bryan Robbins, Sr.

(1896 – 1972)

A Polar Bear in North Russia

by Miriam Robbins Midkiff

It was a humid night in Western Michigan, and the stars and fireflies twinkled over the yard of my great-grandparents’ home where I stood on a small statue of a polar bear. My 10-year-old cousin scolded, “Don’t stand on that! It’s Grandpa’s!” The “grandpa” mentioned was his grandfather and my great-grandfather, William Bryan Robbins, who had recently passed away. It was 1972, I was five years old, and although it was a time of sorrow for many family members, it was a time of magic for me. Just a few days earlier, I had flown 3,000 miles with my parents from our small Alaskan village, population 300, coming into a breathtaking view of Chicago at night, a scene I would never forget. At our journey’s end, my grandfather met us at the airport in Grand Rapids. We drove 35 miles west to tiny Conklin and pulled into the driveway of my great-grandparents’ home. Grandpa said, “Now there’s Great-grandma. She’s feeling sad today, so give her a great big hug.” I flew out of the car, and running across the yard to where my petite ancestor sat, I surprised her with the biggest embrace my small arms could manage!

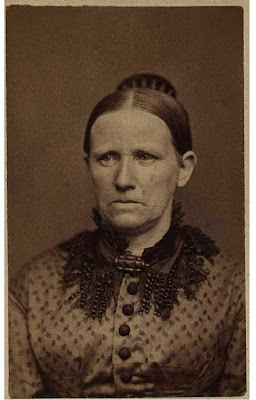

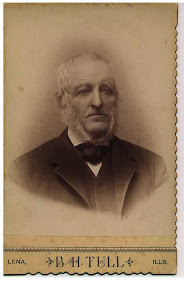

Although our time in Michigan created memories that I still look back on with fondness, I unfortunately have none of the man whose funeral was the purpose behind our trip. I had seen him on two previous visits, but was too young to remember the lean, gray-haired man with an affinity for his pipe and the Robbins’ trademark storytelling. Nor did I have any clue of the significance of the statue in his front yard. Born 6 June 1896 in Hesperia, Michigan, William Bryan Robbins was named for the silver-tongued presidential candidate, William Jennings Bryan. Also known as “Bill” or “Bryan”, he was the third of seven children of Angelo Merrick Robbins and his wife, Mary May “Lula” Kimball. Because Angelo was a schoolteacher, the Robbinses lived all over Newaygo County, wherever a teaching position became available. It wasn’t until 1906 that the family settled in Ensley Township for ten years. Although Bill never attended a higher institute of learning, he continued to educate himself by helping his father study for his annual teaching certifications.

As Bill became a young man, the political climate in Europe geared up for World War I. There were also changes at home. After Bill’s oldest brother died in 1914, the family moved west to Muskegon Heights, a growing community situated three miles inland from Lake Michigan. Here Angelo ended his teaching career and became employed at a nursery, while Bill found work as a chauffeur in the new age of automobiles. One fall day in 1917, Bill was hired to drive a hearse for a funeral. Among the mourners was a blue-eyed, four-foot-eleven, 15-year-old, Marie Lewis. It must have been love at first sight, because they began a courtship that lasted two years. Bill’s older brother, Lloyd, was already serving in France with the 32nd Division in a machine gun corps. So, joining the patriotic spirit that was sweeping the nation, Bill enlisted on 23 June 1918 to begin an unforgettable year in a forgotten expedition in American history.

Like most wars, the events in Northern Russia in the early twentieth century had multiple complicated causes. At the beginning of World War I, Russia was one of the Allies, but was undergoing internal turmoil between the Czarist monarchy, the Provisional Republicans (a democratic party known as White Russians), and the Bolsheviks. When the communists overthrew the Provisional government that succeeded the monarchy, they signed an armistice with Prussia, switching sides mid-war. The Allies were horrified, realizing the enemy could now relocate troops to the Western Front, gaining a three-to-two advantage. The U.S. could also lose a fortune in munitions and foodstuffs it had stored at Murmansk, North Russia, originally intended to help the Allied cause. Things changed when the Bolsheviks realized that they had the disadvantage in their armistice with Prussia, and appealed to the Allies for assistance. Britain saw the opportunity not only to re-establish the Eastern Front, but also to colonize the area. Immense pressure was put upon President Wilson to supply American troops for the expedition, since most British troops were occupied in Western Europe. Ostensibly, Americans were sent to Russia to defend their munitions from Axis takeover. The truth is, the weapons had long been “requisitioned” by Bolsheviks by the time they set foot on Russian soil; and the next 17 months would be a senseless waste of American lives for a purposeless and futile campaign that rivaled the wars of Southeast Asia half a century later.

Bill Robbins’ basic training took place at Camp Custer, Battle Creek, Michigan. He was assigned to Company I of the newly formed 339th Infantry of the 85th Division, later nicknamed the “Polar Bear Division,” because of its service in the American North Russian Expeditionary Force (ANREF). But Russia was the last thing on these Michiganders' minds that summer of ’18. They believed they would join their brothers in the trenches of Western Europe. Leaving in late July, they made their way by train and ship to the south of England, where they had the bad luck to be stationed at the wrong place at the wrong time. General Pershing felt he could not spare any of his troops from France, so he chose the 339th to be assimilated into British schemes. The Americans were re-outfitted with British uniforms, rations, and supplies, which were of lowest quality. Antarctic explorer Ernest Shackleton had designed the outer garments of the uniforms. While constructed to keep out the cold, the soldiers’ safety and agility in battle had not been kept in mind. The overcoats were stiff and unwieldy, the boots’ slippery soles as useful as high heels on frozen terrain. The horrid rations consisted of ancient canned corned beef and seven-year-old frozen rabbit. Medicine was limited to iodine, quinine, and laxatives. The injury to insult was the replacement of reliable, U.S.-made rifles with the Russian Moisin-Nagant 7.62mm rifle, whose poor design and inaccuracy caused soldiers to describe it as being able to “shoot around corners.” Additionally, there was no scabbard for the bayonet, so it had to be permanently fixed to the rifle, making it only useful to roast meat over campfires!

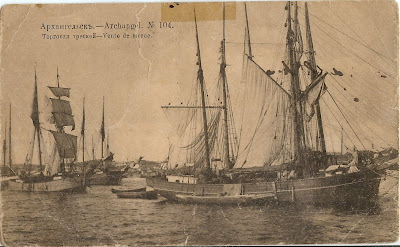

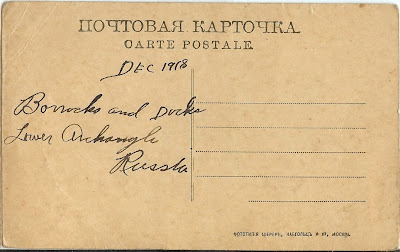

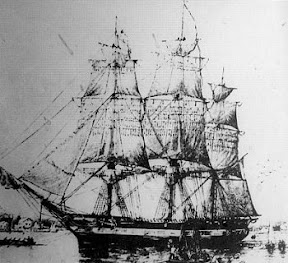

The 339th was sent to Newcastle-on-Tyne, where they embarked for an eleven-day voyage. This transport also included the 310th Engineers, the 1st Battalion, the 337th Ambulance Company and the 337th Field Hospital. The medical training of the latter consisted mainly of learning how to roll bandages. Medical supplies had purposefully been left behind in England to make room for crates of whiskey for British officers. Only a handful of first aid equipment was brought along by some American medics. On their route through the North Sea, influenza took hold, due to one of the ships not being disinfected after its last trip on which it had carried many deadly cases of the illness. Several men died enroute and were buried at sea. When the ships arrived at Archangel on September 7th, a large number of soldiers were ill and had to be quarantined in makeshift hospitals. Four weeks later, the flu ran its course with nearly 100 young men dead and buried in a new cemetery in Archangel. Bill also became ill, but refused to seek medical treatment. He knew that in the contagious atmosphere of the infirmaries his chances of survival were slim. He recovered and was sent to the Railroad Front.

Archangel was then a city of 40,000 inhabitants, located where the Dvina River flows into the White Sea. The surrounding 250,000 square miles are nothing but swampland, with only stunted pine forests breaking up the monotonous landscape. A railroad stretched southward to Moscow for some 900 miles. Several companies, including Company I, were stationed at the Railroad Front, an area of about 125 square miles encompassing both sides of a 17-mile stretch of railroad. Encampments were made along the railroad, and these outposts were defended, along with French troops, from the Bolsheviks (“Bolo”). Besides the French, there were also British and Royal Scots, Italian, Canadian, and Serb troops spread across the province. All were placed under British command; lower-ranking British officers were given authority over other high-ranking officers. The Americans got on well with the other troops, except for the Brits. Unfortunately, the British took advantage of the Americans, even confiscating food, supplies, and gifts sent to them. Many soldiers had to pay to receive goods sent by their own families! Additionally, some in the service organizations stationed in Archangel also joined in to profit in this unethical manner. Bill recalled that he purchased a sweater from the YMCA, which had been made and donated by citizens back home. The Americans were paid in worthless British script; Bill ended up giving away his to a peasant when he left Russia.

The American troops received no help from their superior officers in these matters. ANREF commander, Colonel George Stewart, abdicated his authority to the British command and would not interfere to assist his men. To make matters worse, the major in charge of the 339th was a drunken incompetent. He would send his companies after the enemy without proper intelligence or maps. If they failed in their missions, he would blame them. He so infuriated the enlisted men that he was in danger of losing his life. Bill recalled later some of the men shooting at the chimney of the major’s building to scare him into going back from the front. The saving grace in this situation was the lower-ranking American officers, who did all they could to ease the load of those under them, taking part in their privations. These men often risked receiving reprimands from their superior officers as they defended the enlisted men in courts martial, or refused to obey orders that unnecessarily risked their men’s lives.

Above and beyond all obstacles was the climate, worse than the enemy himself. With the winter of 1918-1919 being one of the coldest on record, the thermometer plunged to 60 below zero. Bill once told how the men would sit on frozen, snow-covered logs near the campfires while they warmed themselves. When the spring thaw hit, they discovered that some of the “logs” were actually corpses! With inadequate clothing and lack of food, the troops looked to the peasants’ ways to survive. They discarded the cumbersome boots for fur moccasins, trapped rabbits, shot wild birds and used grenades to blow fish from the frozen rivers to eat. Always they must stay on the lookout for terrorist attacks. Like the wars in Korea and Viet Nam, our troops could never be sure who was enemy and who was friend.

Meanwhile, the families of the ANREF were appealing to their Congressmen. The Armistice, signed on November 11, 1918, had ended World War I, but their sons were still fighting what seemed an endless war. Finally, an Act of Congress brought the Polar Bears home. Beginning June 3, 1919, the first of the troops shipped out of Archangel for Brest, France. On June 21st, they boarded the

S.S. Von Steuben for their final voyage home, arriving in Detroit on July 3rd. Orders to form ranks and march down the street were disregarded, as families mobbed the platforms to embrace loved ones. On July 7th, the Force demobilized at Camp Custer and headed home. Bill received his discharge pay of $284.45. He was fortunate that he was never wounded, and although he did not receive any medals, he was issued a Bronze Victory button. One hundred twenty-one American dead were left behind in Russian soil for another ten years, until a search party returned with the remains of eighty-six.

As for Bill, he married sweet little Marie whose letters sustained him during the bitter hardship of the north. They were wed Christmas Day 1919 and became the parents of five children. All three sons served in World War II: two in the Army Air Corps, the other in the Navy. Bill’s years after the war are another story; but when he passed away on 6 August 1972 in Grand Rapids, he was survived by his wife of nearly 53 years, five children, ten grandchildren and eight great-grandchildren. As I stood at his grave in Coopersville Cemetery, Ottawa County, Michigan for the first time in October 2000, I marveled at the obstacles this man had overcome thousands of miles away, and I felt proud to be his descendant. Truly, William Bryan Robbins, Sr. is one of my favorite military ancestors!

Sources:

Newaygo County, Michigan Vital Records

Oceana County, Michigan Clerk’s Office

Muskegon County, Michigan Vital Records

1900, 1910, and 1920 U. S. Federal Census Records

Robbins Family Records

Robbins Oral History, as told by Robert Lewis Robbins and Bryan Henry Robbins

Discharge and Enlistment Records of William Bryan Robbins

Quartered in Hell: The Story of American North Russian Expeditionary Force, 1918 –1919 by Dennis Gordon, published by The Doughboy Historical Society and G.O.S., Inc., Missoula, Montana, 1982

“Detroit’s Own” Polar Bears: The American North Russian Expeditionary Forces, 1918 –1919 by Stanley J. Bozich and Jon R. Bozich, published by Polar Bear Publishing Co., Frankenmuth, Michigan, 1985

Other Posts in this Series:

2. The Family of Angelo and Lula Robbins

3. Bryan and Marie - A WWI Romance

4. Bryan Gets Drafted

5. Basic Training at Camp Custer

6. Getting "Over There"

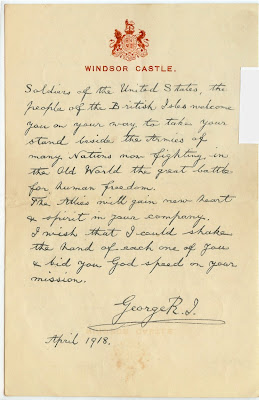

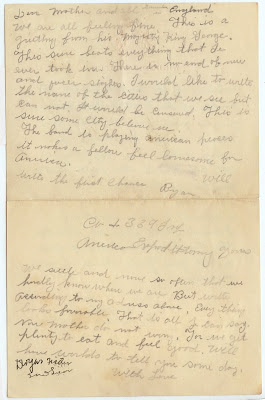

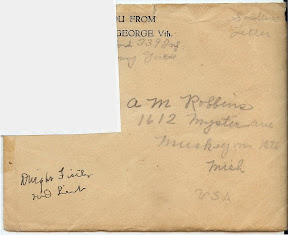

7. Bryan and King George V

8. To Russia, With Influenza

9. A Letter from Mother - 25 Sep 1918

10. A Letter from Father - 7 Oct 1918